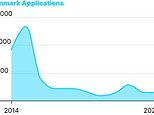

UPDATE: Just announced, the UK Labour Party is embroiled in turmoil as officials debate adopting Denmark’s stringent immigration policies, which have led to a staggering 90 percent drop in asylum applications. Shabana Mahmood, the Home Secretary, is reportedly evaluating Denmark’s system that has driven claims to a 40-year low, with officials sent to Copenhagen to gather insights.

The Labour Party is facing backlash from its left wing, with Nadia Whittome, a prominent member, condemning the Danish model as “undeniably racist.” She warns that such policies are more aligned with far-right ideologies than with those of a centre-left party. The divide highlights increasing pressure on Keir Starmer to address rising small boat crossings, which reached 36,954 this year alone.

Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has made strict immigration control a central promise since taking office in 2019. Her approach, which includes no benefits for rejected asylum seekers and the requirement for migrants to surrender valuables to cover their stay, has been deemed effective. Last year, Denmark recorded just 2,333 asylum applications, a stark contrast to the UK’s record high of 111,100.

Denmark’s policy framework mandates that asylum is only granted temporarily, with refugees expected to return when their home countries are deemed safe. The system also stipulates that permanent residency requires at least eight years of steady employment and compliance with integration rules, including mandatory language learning.

Asylum seekers who do not qualify are placed in deportation centers, where they receive basic meals but no cash benefits. To further discourage dependency, Denmark offers financial incentives of up to £24,000 for voluntary return to home countries. Critics argue that these policies create a chilling effect on those genuinely seeking refuge.

The Labour Party is reflecting on whether to embrace these policies as public trust in immigration management declines. While some members, like Gareth Snell from Stoke-on-Trent Central, advocate for learning from Denmark’s strategies, others warn against any alignment with measures seen as discriminatory.

In Denmark, the integration of newcomers is strictly enforced, including a ban on burkas in public spaces, which the government argues is vital for societal cohesion. The Danish model has allowed mainstream parties to neutralize far-right sentiments, with the Social Democrats remaining highly popular among voters.

As UK immigration challenges persist, including failed attempts at offshore processing and rising illegal crossings, pressure mounts on Starmer to present viable solutions. The stark contrast between Denmark’s success and the UK’s struggles raises questions about Labour’s future direction on immigration policy.

The ongoing debate within the Labour Party is crucial. Mahmood faces the daunting task of convincing her colleagues to adopt tougher immigration controls that might alienate some party factions. Whether Labour can muster the resolve to implement decisive changes could reshape its credibility with voters who demand effective immigration management.

As the situation develops, all eyes will be on the Labour Party’s next steps and whether they can adopt a balanced approach that addresses both public concern and humanitarian needs.