Researchers in Germany and Italy have made a significant advancement in quantum physics by observing Shapiro steps in ultracold gases for the first time. This phenomenon, characterized by abrupt changes in the voltage-current relationship of a Josephson junction exposed to microwave radiation, offers new insights into quantum mechanics and could establish a reference standard for chemical potential.

The concept of Josephson junctions originated in 1962, when Brian Josephson from the University of Cambridge theorized that a phase difference between wavefunctions across a thin insulating barrier would induce quantum tunneling. A year later, Sidney Shapiro and colleagues demonstrated that alternating electric currents generated by microwave fields lead to quantized increases in potential difference across the junction. The height of these Shapiro steps is determined solely by the frequency of the applied field and the electrical charge, forming the basis of a standard for voltage reference.

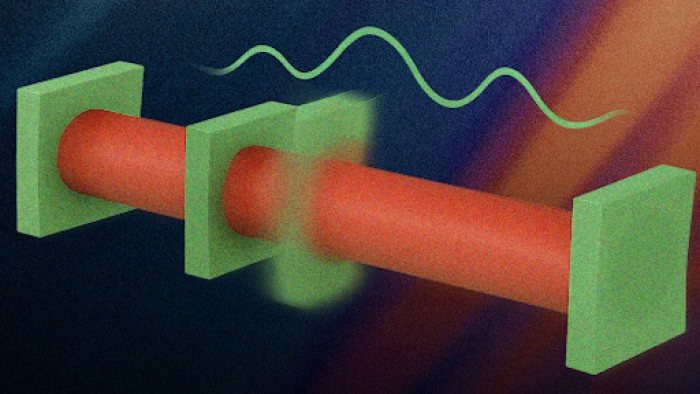

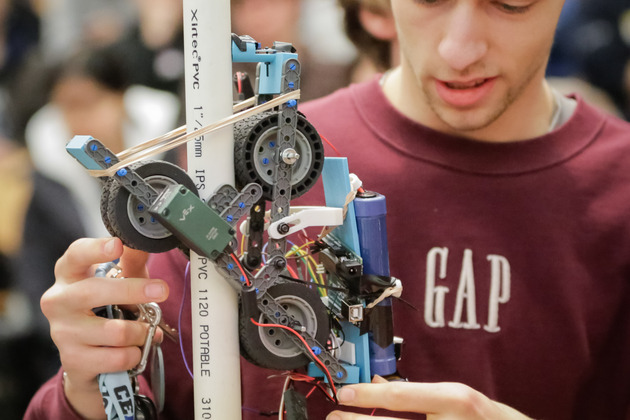

In their groundbreaking work, two independent research teams observed Shapiro steps in ultracold quantum gases, moving beyond traditional superconductors. Instead of a fixed insulator, the researchers utilized focused laser beams to create potential barriers that divided atomic traps, allowing for the manipulation of atomic positions and potentials.

Herwig Ott from RPTU University Kaiserslautern-Landau, who led one of the studies, explained the process: “If we move the atoms with a constant velocity, that means there’s a constant velocity of atoms through the barrier. This is how we emulate a DC current.” To achieve the AC current necessary for the Shapiro protocol, the team modulated the barrier in time.

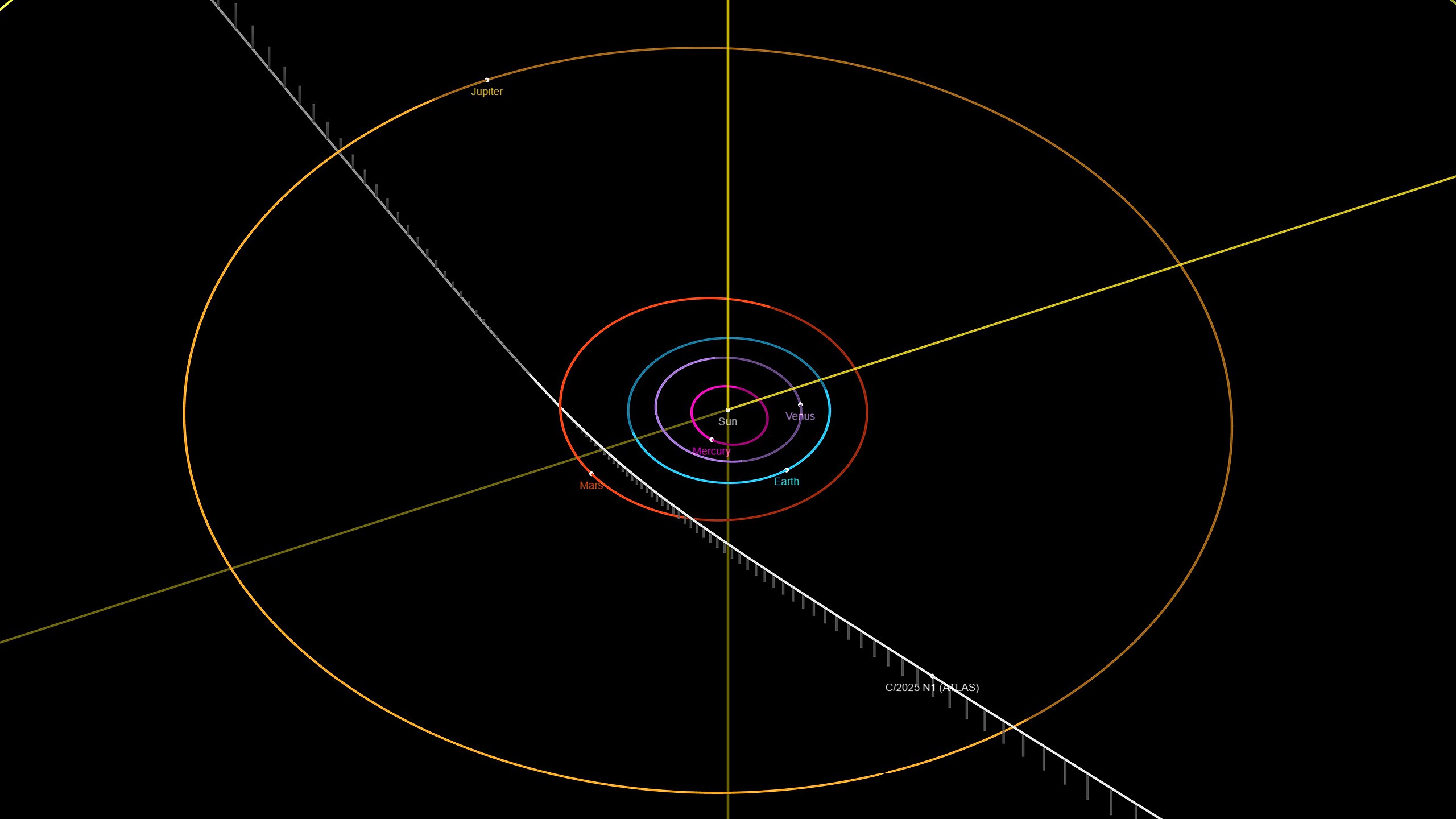

The team in Kaiserslautern collaborated with researchers from Hamburg and the United Arab Emirates, employing a Bose–Einstein condensate of rubidium-87 atoms. Meanwhile, in Italy, Giulia Del Pace of the European Laboratory for Nonlinear Spectroscopy at the University of Florence, along with her colleagues, investigated ultracold lithium-6 atoms, which are categorized as fermions.

Both groups successfully observed the predicted Shapiro steps, but they emphasized that their findings extend beyond mere confirmation of theoretical models. “The message is that no matter what your microscopic mechanism is, the phenomenon of Shapiro steps is universal,” stated Ott. In superconductors, these steps arise from the breaking of Cooper pairs, while in ultracold atomic gases, vortex rings are produced. Despite these differences, the underlying mathematics remains consistent.

Del Pace noted the uncertainty surrounding the observation of Shapiro steps in strongly-interacting fermions, which present a different dynamic than the electrons in superconductors. “Is it a limitation to have strong interactions or is it something that actually helps the dynamics to happen? It turns out it’s the latter,” she remarked. Her research team manipulated a variable magnetic field to transition their system between a Bose–Einstein condensate of molecules, dominated by Cooper pairs, and a unitary Fermi gas characterized by maximum allowed interparticle interaction.

Both Ott and Del Pace propose that their findings could pave the way for a new reference standard for chemical potential, which measures the strength of atomic interactions. Del Pace elaborated, “This equation of state is very well known for a BEC or for a strongly interacting Fermi gas, but there is a range of interaction strengths where the equation of state is completely unknown.”

The results of these studies are published in the journal Science, highlighting the significance of their parallel research efforts. Rocío Jáuregui Renaud from the Autonomous University of Mexico expressed admiration for the dual demonstration of Shapiro steps in both bosonic and fermionic systems. “The two papers are important, and they are congruent in their results, but the platform is different,” she noted.

The implications of this research extend beyond superconductivity, offering fresh insights into phenomena that can be observed in neutral atoms but may remain hidden in electronic systems. As researchers continue to explore these ultracold gases, the potential for groundbreaking discoveries in quantum mechanics and material science remains immense.