The examination of ancient military thought reveals profound insights into the relationship between technology and warfare, as illustrated by the work of the historian Thucydides. In an interview with Bret C. Devereaux, a Teaching Assistant Professor at North Carolina State University, the discussion centers on how Thucydides’ writings serve as a crucial guide for understanding the human dimension of military strategy, particularly during periods of significant technological evolution.

Thucydides, often regarded as a founding figure of historical analysis, sought to explain historical events through human actions and motivations rather than divine intervention. His account of the Peloponnesian War is frequently interpreted as documenting a static military paradigm dominated by heavy infantry hoplites. This view posits that the conflict marked the decline of a long-established Greek military system that began in the 700s and 600s BCE. Scholars have traditionally viewed this period as one where decisive battles took precedence, with minimal emphasis on technology or tactical innovation.

However, recent scholarship challenges this characterization. Scholars such as Peter Krentz, Hans van Wees, Fernando Echeverría, and Roel Konijnendijk argue that the hoplite-centric warfare Thucydides describes evolved gradually from earlier traditions, beginning in the eighth century BCE and continuing through the Persian Wars (492-479 BCE). They contend that many tactical innovations attributed to Thucydides were, in fact, continuations of existing practices rather than entirely new developments.

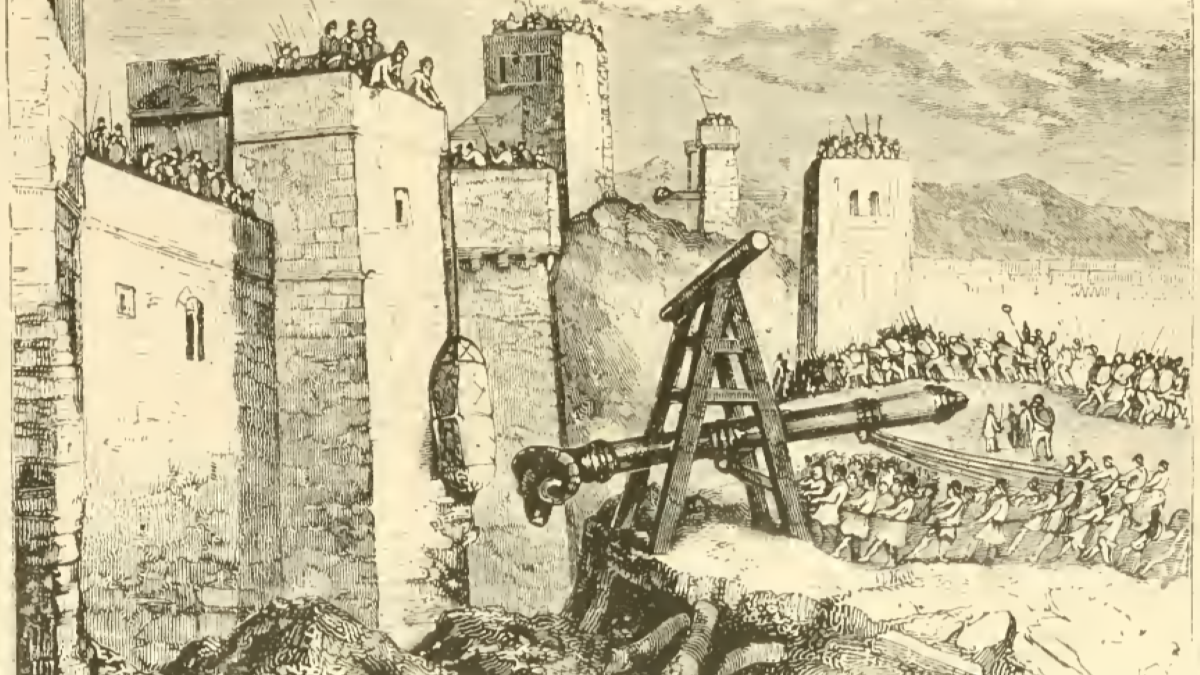

As a result, Thucydides is seen as chronicling a time of transformation, not a sudden shift in warfare. His work captures the initial signs of evolving military strategies, which would later manifest more clearly in the writings of Xenophon and the complexities of fourth-century warfare, characterized by advancements like catapults and larger warships.

Human Elements in Warfare

Thucydides’ writings reveal his acute awareness of the immense scale and consequences of warfare. He describes the conflict as “the greatest shift for the Greeks and some part of the barbarians,” expressing astonishment at military disasters, including the surrender of Spartans at Pylos and the catastrophic Athenian expedition to Sicily. Importantly, Thucydides distinguishes between technological advancements and the evolving human factors influencing conflict.

His account begins with a deep historical context known as the Archaeology, highlighting the emergence of key technologies, such as naval forces and fortified cities. Despite these mentions, Thucydides does not perceive any significant technological innovations during his lifetime. He acknowledges few changes in warfare materials, noting instances such as the exceptional use of a large bellows to set fire to an Athenian fort.

The overall stability of weapons and tactics during the fifth century BCE contrasts sharply with the escalating human dynamics of warfare. The frequency of sieges increased, along with the complexity of tactics, larger armies, and escalating violence, leading to the destruction of entire cities. Thucydides illustrates this evolution through meticulous descriptions of sieges, which indicate a growing willingness among Greek states to invest resources and time in prolonged military operations.

War as a Business

Thucydides’ perspective on warfare can also be viewed through a financial lens. He portrays war as a financial undertaking where money serves as the primary resource to acquire necessary materials for conflict. The demand for resources, particularly during extensive naval operations, is evident in his accounts, although he often focuses on the financial implications rather than the logistical specifics of shipbuilding or weapon production.

He meticulously documents Athens’ revenues and financial transactions, emphasizing the economic dimensions of military endeavors. The Athenian navy, supported by tribute from conquered states, illustrates how war operated as a financial enterprise, facilitating the funding of military campaigns and public works.

In contrast to Thucydides, later historians like Polybius documented periods marked by significant technological advancements and asymmetrical warfare. Polybius’ accounts reflect a keen interest in the specifics of military technology, such as the Roman adoption of foreign innovations, a stark contrast to Thucydides’ relatively stable descriptions of Greek military operations.

Ultimately, Devereaux’s insights into Thucydides’ work highlight the historian’s nuanced understanding of the interplay between technology and human elements in warfare. While technological advancements were limited during Thucydides’ time, the evolving political landscape and the shifting dynamics of human behavior played a crucial role in shaping the course of the Peloponnesian War. This examination underscores the importance of viewing historical narratives through multiple lenses to fully grasp the complexities of war and statecraft.