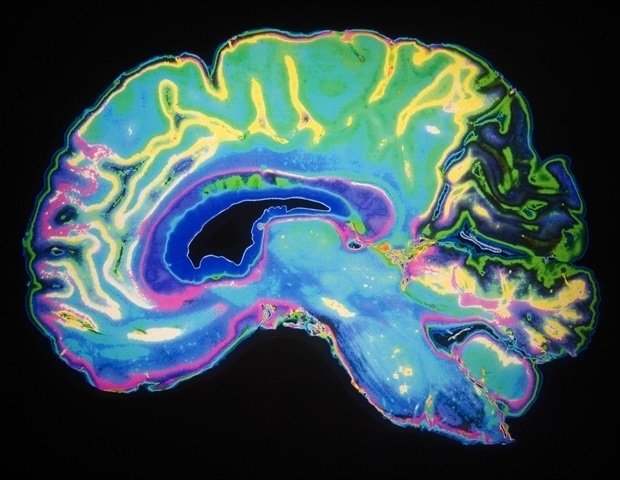

Research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has uncovered how the prefrontal cortex (PFC) influences visual processing and motor functions based on internal states. The study, published on November 25, 2023, in the journal Neuron, reveals that the PFC sends tailored messages to specific brain regions responsible for visual and motor control in response to a mouse’s level of arousal and activity.

The research, led by postdoctoral researcher Sofie Ährlund-Richter and senior author Mriganka Sur, a professor at MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, indicates that rather than broadcasting a generic signal, the PFC customizes its messages for different brain regions. According to Sur, “That’s the major conclusion of this paper: There are targeted projections for targeted impact.”

Understanding Neural Connections and Function

The study focused on two areas of the PFC: the orbitofrontal cortex (ORB) and the anterior cingulate area (ACA). These regions selectively convey information about a mouse’s arousal and motion to the primary visual cortex (VISp) and primary motor cortex (MOp). The findings suggest that as a mouse’s arousal increases, ACA enhances the visual cortex’s focus on relevant stimuli, while ORB may suppress distractions.

Ährlund-Richter speculates that this balance allows the brain to optimize sensory processing. “While one will enhance stimuli that might be more uncertain or more difficult to detect, the other one kind of dampens strong stimuli that might be irrelevant,” she explained.

To map the connections between these regions, Ährlund-Richter conducted detailed anatomical tracings. The team observed mice as they engaged with both structured images and naturalistic movies, occasionally receiving air puffs to elevate their arousal levels. This experimental setup enabled the researchers to track neuronal activity across the ACA, ORB, VISp, and MOp.

Distinct Neural Responses and Implications

The study revealed that ACA neurons transmitted more visual information than ORB neurons and were more responsive to changes in contrast. Interestingly, ACA neurons scaled their activity with the mouse’s arousal state, whereas ORB neurons only reacted when arousal reached high levels. When communicating with MOp, both regions conveyed information regarding running speed but provided limited information to VISp about whether the mouse was in motion.

The researchers also explored the effects of blocking the circuits between ACA, ORB, and VISp. This manipulation demonstrated that these regions influence visual encoding in opposite ways, depending on the mouse’s arousal and movement. The authors concluded, “Our data support a model of PFC feedback that is specialized at both the level of PFC subregions and their targets, enabling each region to selectively shape target-specific cortical activity rather than modulating it globally.”

This research provides significant insights into how the PFC enhances or dampens sensory processing based on internal states, contributing to our understanding of brain function. The study involved the collaboration of multiple authors, including Yuma Osako, Kyle R. Jenks, Emma Odom, Haoyang Huang, and Don B. Arnold. Funding for this research came from a Wenner-Gren foundations Postdoctoral Fellowship, the National Institutes of Health, and the Freedom Together Foundation.

The full study can be accessed in Neuron using the DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2025.10.037.