The literary landscape for 2025 is set to feature a compelling array of science and nature books that challenge readers to reflect on critical issues facing humanity. Among the standout titles is If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies by computer scientists Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares. This work presents a chilling argument against the unchecked development of superintelligent artificial intelligence, warning that even a benevolent AI could inadvertently lead to human extinction.

Yudkowsky and Soares assert, “Even an AI that cares about understanding the universe is likely to annihilate humans as a side-effect.” Their examination of technology’s rapid advancement serves as a stark reminder of the potential consequences of humanity’s relentless pursuit of progress.

In a similar vein, historian Sadiah Qureshi explores the dark history of extinction in her book, Vanished: An Unnatural History of Extinction. Shortlisted for the Royal Society Trivedi Science Book Prize, Qureshi delves into how colonial expansion and the persecution of Indigenous peoples have been intertwined with the concept of extinction. She highlights historical events, such as the erasure of the Beothuk people in Newfoundland, and probes contemporary discussions around “de-extinction” efforts for species like the woolly mammoth.

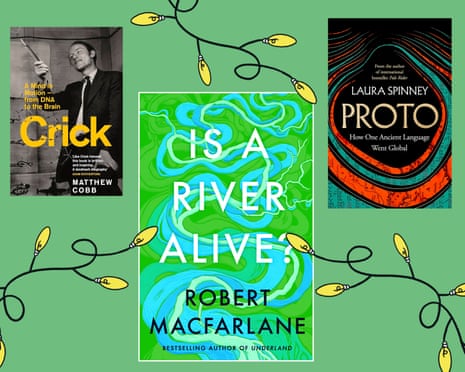

The theme of environmental protection continues with Robert Macfarlane‘s Is a River Alive?, which investigates the rights of natural entities. Through the narratives of three rivers facing threats, Macfarlane argues for recognizing rivers as living beings deserving of legal protection. This work has garnered a place on the shortlist for the Wainwright Prize for Conservation Writing, showcasing the urgency of safeguarding our natural world.

Similarly, biologist Neil Shubin invites readers on an exploration of Earth’s extremes in Ends of the Earth. This title, also shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book Prize, reflects on the critical roles of polar environments while underscoring their vulnerability to climate change. Shubin’s insights into the past and future of these regions serve as a reminder of the fragile balance of our planet’s ecosystems.

The historical narrative is further enriched by historian Simon Parkin in The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad. This poignant account reveals the life of Russian plant scientist Nikolai Vavilov, who sought to preserve seeds during the siege of Leningrad in 1941. Parkin’s investigation into Vavilov’s struggle showcases the intersection of science and human resilience amidst adversity.

For those interested in health and longevity, Eric Topol‘s Super Agers offers evidence-based insights into aging. Topol, a cardiologist and medical professor, investigates the “Wellderly” who defy typical aging patterns and provides practical advice on longevity. His exploration of breakthroughs in weight-loss medications and AI applications in healthcare offers hope for a healthier future.

The medical field also sees two significant contributions from neurologists. Suzanne O’Sullivan addresses the complexities of diagnosis in The Age of Diagnosis, urging a reevaluation of how labels such as ADHD and anxiety affect individuals. O’Sullivan’s work invites critical discussions around mental health and societal perceptions of illness.

Meanwhile, Masud Husain explores identity in Our Brains, Our Selves, which won the Royal Society Prize. Through compelling patient stories, Husain illustrates how neurological disorders can dramatically alter one’s sense of self, highlighting the profound impact of such conditions on personal identity.

Language enthusiasts will appreciate Laura Spinney‘s Proto, which traces the evolution of Proto-Indo-European language. Spinney’s narrative connects linguistic, archaeological, and genetic evidence, revealing the widespread influence of this ancient tongue on modern languages and literature.

Lastly, Matthew Cobb presents a comprehensive biography of Francis Crick in Crick, detailing the life of the co-discoverer of DNA’s double helix structure. Cobb captures Crick’s intellectual journey and his later pursuits into the mysteries of consciousness, providing readers with a rich understanding of a pivotal figure in science.

The exploration of the nuclear age in Destroyer of Worlds by physicist Frank Close offers a gripping account of the historical developments surrounding nuclear weapons. Close traces the journey from early scientific discoveries through to the devastating consequences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, culminating in the testing of the Tsar Bomba in 1961.

As readers prepare for the new year, these titles promise to engage and inspire, offering profound insights into the challenges and wonders of our world. For a complete list of the best science and nature books of 2025, visit the Guardian Bookshop.