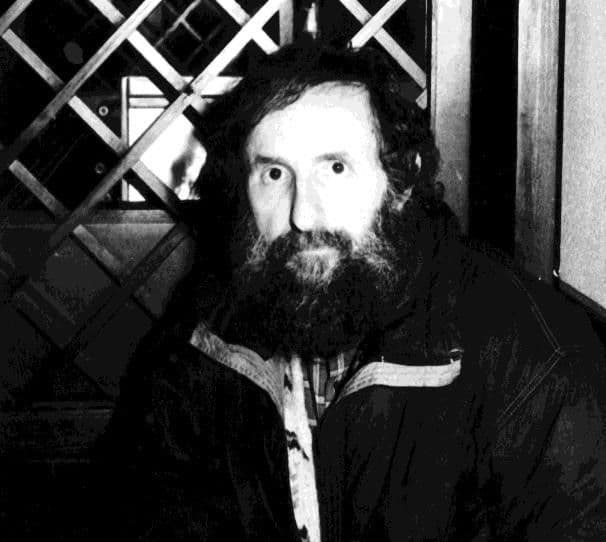

The acclaimed cinematographer Živko Nikolić has encountered significant challenges in his life following the release of the film U ime naroda. Despite his talent and contributions to the Montenegrin film industry, his personal circumstances have taken a turn for the worse.

In an interview, Savo Radunović, director of the film Jovana Lukina, shared insights into the demanding conditions under which the film was shot. Located near the Ostrog Monastery, the rugged terrain posed numerous challenges for the crew. “We began filming in early spring, during which the green landscape transformed,” Radunović explained. This transformation required the team to artificially paint the surroundings black to achieve the desired visual effects.

The filming process was further complicated by an earthquake that struck the area, causing rocks to fall from the cliffs. “There wasn’t a shot that Živko didn’t oversee,” Radunović noted, emphasizing Nikolić’s reputation as one of the best cinematographers in the country. His expertise in lighting allowed him to create stunning visuals, often transforming ordinary subjects into striking images.

Despite the film’s artistic success, it appears that the political climate at the time hindered its acceptance. Radunović expressed his belief that Jovana Lukina is one of Nikolić’s finest works, beautifully composed and expertly shot, yet it received limited support from the authorities.

Filming for U ime naroda took place in Nikšić, specifically in a neighborhood named after the national hero Buda Tomović. This setting, described as a “horror neighborhood,” reflected the harsh realities faced by workers from the local steel mill and Roma communities. The crew faced challenges in recreating this environment, yet the local residents were incredibly supportive, showcasing resilience despite their struggles.

The next project, titled Iskušavanje đavola, was filmed above Petrovac in a restored abandoned tower. This film incorporated themes of familial conflict and romantic turmoil, set against the backdrop of traditional Montenegrin life. According to Radunović, this project was well-received by audiences, resonating with viewers through its multifaceted storytelling.

Regrettably, in the wake of U ime naroda, Nikolić’s life took a downward trajectory. He faced severe difficulties, including poor health and financial instability. “He struggled to find enough to eat and live adequately,” Radunović recounted. Nikolić was forced to sell his apartments to make ends meet, highlighting the harsh reality many artists face.

Despite his artistic contributions, Nikolić encountered hostility from colleagues and the film community. Some believed that his work caricatured Montenegrin culture, leading to a lack of acceptance both in Montenegro and in neighboring Serbia. “Živko worked for Montenegro and around Montenegro, yet he did not receive support during his toughest times,” Radunović lamented, reflecting on the lack of recognition for Nikolić’s contributions.

As the film industry continues to evolve, there remains hope that the legacy of artists like Živko Nikolić will be recognized and celebrated, ensuring that their contributions are not forgotten. The struggles faced by such talents raise essential questions about the support systems in place for artists within their communities.