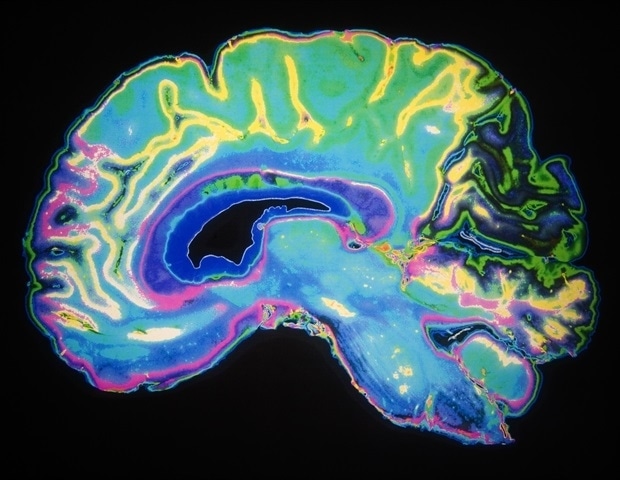

Recent research from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg (FAU) has revealed that functional MRI (fMRI) signals can often misrepresent true brain activity. The study indicates that in approximately 40 percent of cases, an increased fMRI signal correlates with reduced brain activity, challenging a fundamental assumption in neuroscience.

The conventional belief has been that increased brain activity leads to enhanced blood flow, thereby meeting the oxygen demands of active neurons. However, this research highlights a more complex relationship between blood flow and brain activity. The findings suggest that decreased fMRI signals can occur in regions where brain activity is actually heightened, indicating a need for a reassessment of how fMRI results are interpreted across numerous studies.

Research Findings and Methodology

The study involved over 40 healthy participants who were given tasks that typically produce predictable fMRI signal changes, such as mental arithmetic and autobiographical memory recall. During these tasks, the researchers employed a novel quantitative MRI technique to simultaneously measure actual oxygen consumption.

The results varied depending on the task and the specific brain region. For instance, areas engaged in calculation showed increased oxygen consumption without corresponding increases in blood flow. Instead, these regions were found to extract more oxygen from a stable blood supply, using the available oxygen more efficiently without necessitating greater perfusion. This discovery has significant implications for understanding brain function and energy metabolism.

Implications for Neuroscience and Clinical Research

According to PD Dr. Valentin Riedl, now a professor at FAU, these insights could alter interpretations in research on brain disorders, including depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Many existing studies have relied on blood flow changes as indicators of neuronal activation. Given the limitations of these measurements, Riedl suggests that researchers must reevaluate their findings, particularly in patient groups affected by vascular changes due to aging or disease.

Previous animal studies have hinted at similar conclusions, reinforcing the need for a shift in methodology. The researchers advocate for integrating quantitative measurements with traditional fMRI approaches. This combination could pave the way for energy-based brain models that focus on actual energy consumption rather than relying on blood flow assumptions. By tracking how much oxygen is consumed during information processing, future analyses may provide more accurate insights into aging, psychiatric conditions, and neurodegenerative diseases.

The research findings were published in the journal Nature Neuroscience on March 15, 2025, under the title “BOLD signal changes can oppose oxygen metabolism across the human cortex.” This study raises important questions about the validity of existing fMRI studies and offers a new perspective on brain activity interpretation that could reshape future neuroscience research.